Indian Bend Wash Greenbelt: A Chronological History

Before the 1960s:

A Flood-Prone Natural Wash

Long before development, the Indian Bend Wash was a natural desert floodplain (locally nicknamed “the Slough”). Heavy rains would turn this brush-choked arroyo into a temporary river, cutting the area in two. Early Scottsdale farmers even noted how floodwaters slowly bent their crops without washing them away. By the mid-20th century, as Scottsdale grew, this marshy lowland routinely overflowed during storms – roads became impassable and even schools closed when the wash flooded. The stage was set for a solution to this decades-old flooding problem.

Early 1960s:

Plans for a Concrete Channel

In 1961, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed a drastic fix: a massive concrete flood channel straight through Scottsdale. The original plan envisioned a 7-mile long, 150-foot wide, 25-foot deep cement ditch, similar to the Los Angeles River’s channel. This “intermittent moat” would efficiently carry stormwater, but it would also create a sterile gash splitting the city. Local officials initially backed the cost-effective plan, and funds were earmarked to begin work. However, many residents were alarmed at the thought of a giant concrete trench dividing their community.

Mid-1960s:

A Community Envisions a Greenbelt

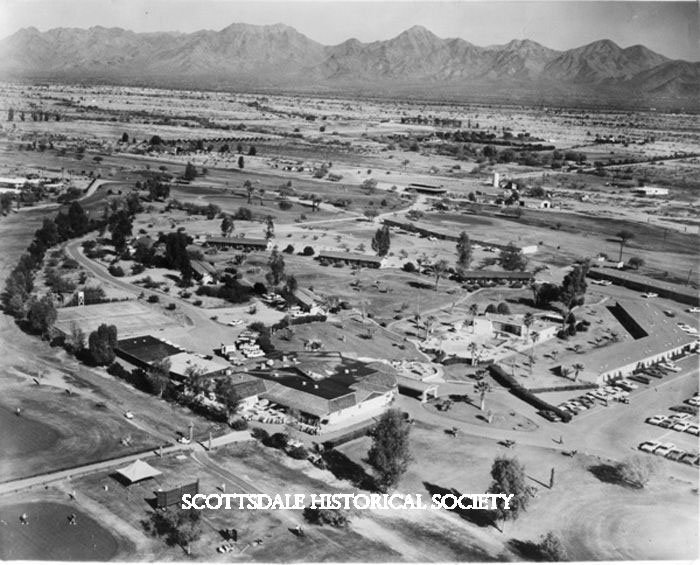

Scottsdale citizens soon rallied around an alternative vision for the Indian Bend Wash. In February 1964, a young landscape architect named Bill Walton published a bold proposal in the Scottsdale Progress newspaper. Biking through the muddy wash to work, Walton had observed that while floods swept away dirt and gravel, the grass on a nearby golf course stayed intact. His article urged Scottsdale to “think beyond” the Army’s utilitarian ditch and imagine a linear park – a greenbelt similar to New York’s Central Park – running right down the wash. The idea of a multi-use floodway that could double as recreation space “staggered the imagination with all the possibilities,” he wrote.

Walton’s visionary idea struck a chord. The very next night, two City Council members knocked on his door and asked him to lead a committee to study the concept. This moment sparked what became a broad grassroots effort. Hundreds of residents joined the Scottsdale Town Enrichment Program (STEP), a citizen-led forum from 1965 to 1974 that championed projects like the greenbelt, trails and parks as part of Scottsdale’s General Plan. Backed by this shared community vision (and many 7–0 votes of support in City Council), Scottsdale began pursuing the greenbelt idea in earnest. In 1967 the city opened Eldorado Park – its first major park – on donated land in the wash, as a prototype of the proposed greenbelt. This early success was made possible by creative city planning; Scottsdale even allowed developers to transfer building density out of the floodplain in exchange for dedicating land to the park, helping assemble the needed open space. By the late 1960s, the Indian Bend Wash project was taking shape on paper, but it still faced financial and political hurdles before becoming reality.

1970–1972:

Floods Strengthen the Resolve

Nature soon tested Scottsdale’s resolve. In September 1970, a Labor Day storm drenched the region, and Indian Bend Wash swelled to nearly 1,000 feet wide – so wide that it burst the banks of the Arizona Canal and flooded adjacent neighborhoods. Two years later, record rainfall struck again in 1972, inundating homes and streets along the wash. These floods underscored the urgent need for flood control. They also shifted public opinion decidedly in favor of the greenbelt solution. Skeptics had earlier questioned the ambitious plan’s cost, and initial bond measures to fund construction were rejected, stalling progress in the late 1960s. But after the destructive 1972 flood, Scottsdale voters overwhelmingly approved a new bond issue (by a 7-to-1 margin) to finance the greenbelt project. “Mother Nature” had provided a compelling argument, and at last the community had the money to move forward.

1973–1980s:

Building the Indian Bend Wash Greenbelt

With funding secured, Scottsdale broke ground on the Indian Bend Wash Greenbelt in 1973. What followed was a decade-long transformation of the barren wash into a vibrant network of parks and lakes. Engineers and landscape planners carefully contoured the natural channel to safely contain and direct floodwaters. Instead of lining it with concrete, they planted grass and trees to stabilize the soil, knowing vegetation would survive routine flows and help absorb runoff. A continuous series of recreational amenities took shape: ball fields, playgrounds, fishing lakes, and golf courses were constructed at intervals along the wash. By integrating recreation, the flood control project became an 11-mile “emerald necklace” of green space through Scottsdale’s heart. The design even incorporated public art – for example, Scottsdale installed “Water Mark” equine sculptures that spout water from their mouths during flash floods, a nod to the area’s ranching heritage. Throughout the 1970s, various segments of the Greenbelt opened to the public as work progressed piece by piece.

This collaborative undertaking involved all levels of government and the private sector. Federal, state, county and local funds (as well as land contributions from private landowners) financed different sections. Progress was steady but measured; it took time to negotiate land acquisitions and meet engineering requirements set by the Army Corps. The effort earned national recognition even before it was finished – in 1974 the American Society of Civil Engineers named Scottsdale’s greenbelt one of the nation’s top engineering achievements. By 1984, the primary construction was complete. What had once been written off as an “unbuildable no-man’s land” was now a chain of lush parks, ponds, and pathways threading through the city. (The final link, a new golf course at the southern end, opened in 1999 – marking the full realization of the continuous Greenbelt vision.)

1990s:

Expansion and Modernization

By the 1990s, the Indian Bend Wash Greenbelt had become a nationally recognized model for flood control, drawing urban planners from across the country to study its success. As Scottsdale continued to grow, new amenities and sports complexes were added, including expanded recreational facilities at Eldorado and Chaparral parks. The Vista del Camino Disc Golf Course was introduced in the mid-1990s, providing a unique recreational option for residents and visitors alike. Responding to the needs of Scottsdale’s youth, the city also built The Wedge Skate Park at Eldorado Park, giving skateboarders a dedicated and hassle-free space. Public art installations continued to enrich the Greenbelt, with sculptures, murals, and decorative bridges enhancing the scenic landscape. Meanwhile, golf courses within the wash, such as Coronado and Continental Golf Course, remained popular, offering affordable and accessible golfing opportunities for the community.

2000s:

Environmental and Community Enhancements

In 2004, the Indian Bend Wash Greenbelt received significant recognition when the Arizona Chapter of the American Public Works Association named it one of the Top 10 Public Works Projects of the 20th Century. The Greenbelt continued to evolve, balancing recreation with environmental sustainability. One major change was the conversion of the former Villa Monterey Golf Course into Camelback Park in 2008, adding even more green space to the floodplain. Around this time, Scottsdale introduced its first dedicated off-leash dog park at Chaparral Park, catering to the city’s growing pet-friendly community.

A focus on accessibility and wellness led to the installation of fitness stations and wheelchair-accessible exercise paths, ensuring that residents of all abilities could enjoy the Greenbelt’s outdoor spaces. The Greenbelt’s lakes also saw improvements, with better water circulation and the expansion of fishing programs that enhanced wildlife habitats and created new opportunities for anglers. Throughout the decade, Scottsdale made a concerted effort to maintain and improve the Greenbelt’s pathways, solidifying its role as a vital part of the city's bicycle commuting network.

2010s–Present:

Sustainability and Long-Term Impact

The Indian Bend Wash Greenbelt has continued to prove its resilience and value well into the 21st century. In 2014, a major storm event tested the system, and the Greenbelt successfully absorbed the floodwaters with minimal damage, reinforcing its long-term effectiveness. Scottsdale placed an increased emphasis on sustainability and water conservation, leading to improvements in irrigation systems and landscaping throughout the Greenbelt. More shade structures, picnic areas, and playground upgrades were added, making the space even more inviting for families and visitors.

As Scottsdale expanded its biking infrastructure, the Greenbelt’s multi-use path became a major component of the Valley’s larger bike network, offering a safe and scenic route for both commuters and recreational riders. In 2023, the Greenbelt received national recognition in urban planning studies as a successful example of integrating recreation with stormwater management. Today, it remains one of Scottsdale’s most cherished outdoor spaces, seamlessly blending natural beauty with smart urban design.

Legacy:

Hazard to Greenbelt

The conversion of Indian Bend Wash from a flood-prone liability into a thriving greenbelt stands as a landmark achievement in urban planning. The completed Greenbelt now safely carries floodwaters while serving as Scottsdale’s outdoor crown jewel. Instead of an unsightly concrete canal, residents and visitors enjoy an oasis of lakes, lawns, trails, and parks that not only enhance quality of life but also function as a vital drainage system.

Over time, the Greenbelt’s success has been undeniable. Today, more than 63,000 people live within walking distance of its parks and golf courses, and hundreds of thousands use its multi-use paths each year for biking, jogging, and outdoor recreation. What was once a barren and overlooked stretch of land is now widely regarded as one of the best urban green spaces in the country.

The story of the Indian Bend Wash Greenbelt is one of vision, perseverance, and community collaboration. It serves as a testament to Scottsdale’s foresight and determination—transforming a natural disaster risk into an 11-mile-long public amenity that continues to protect the city while enriching the lives of its residents.